If United States Navy Forrest Sherman-class destroyers could talk, well, this one would have a few stories to tell.

The tale of one of the 20th century’s major turning points is familiar. The USS Turner Joy, along with the USS Maddox, were at the center of the 1964 Tonkin Gulf Incident, in which the two destroyers purportedly came under attack by North Vietnamese torpedo boats while sailing in the strait between Hainan Island and the coastline of Nghệ An and Hà Tĩnh provinces. In July, the Maddox had been patrolling offshore from the Democratic Republic of Vietnam on a DESOTO mission whose purpose was to collect and relay signals intelligence to Saigon. Since early 1964 the Army of the Republic of Vietnam had been running covert patrol boat missions and commando raids that targeted northern installations on small islands in the area. Tensions in the Gulf of Tonkin and along the DRV coast were already high in the summer of 1964.

We now know that the US Navy was both monitoring communications and identifying targets in support of these ARVN commando operations. American warships on DESOTO missions often provocatively sailed well within DRV territorial waters, sometimes as close as 14 kilometers offshore, which was well within range of a destroyer’s deck guns.[1] A day or so after an ARVN gunboat raid on a DRV radar installation on Thanh Hóa province’s Hòn Mê island, the Maddox did a close-shore sail near Hòn Mê. Hanoi mobilized three torpedo boats and two gunboats from navy bases in Quảng Ninh and Nghệ An provinces to pursue the Maddox, and on 2 August 1964 they caught up with the destroyer about 40 kilometers offshore. The vessels fired torpedoes, but the destroyer returned their fire, evaded the attack, and with the help of aircraft from the nearby carrier USS Ticonderoga, damaged one torpedo boat.

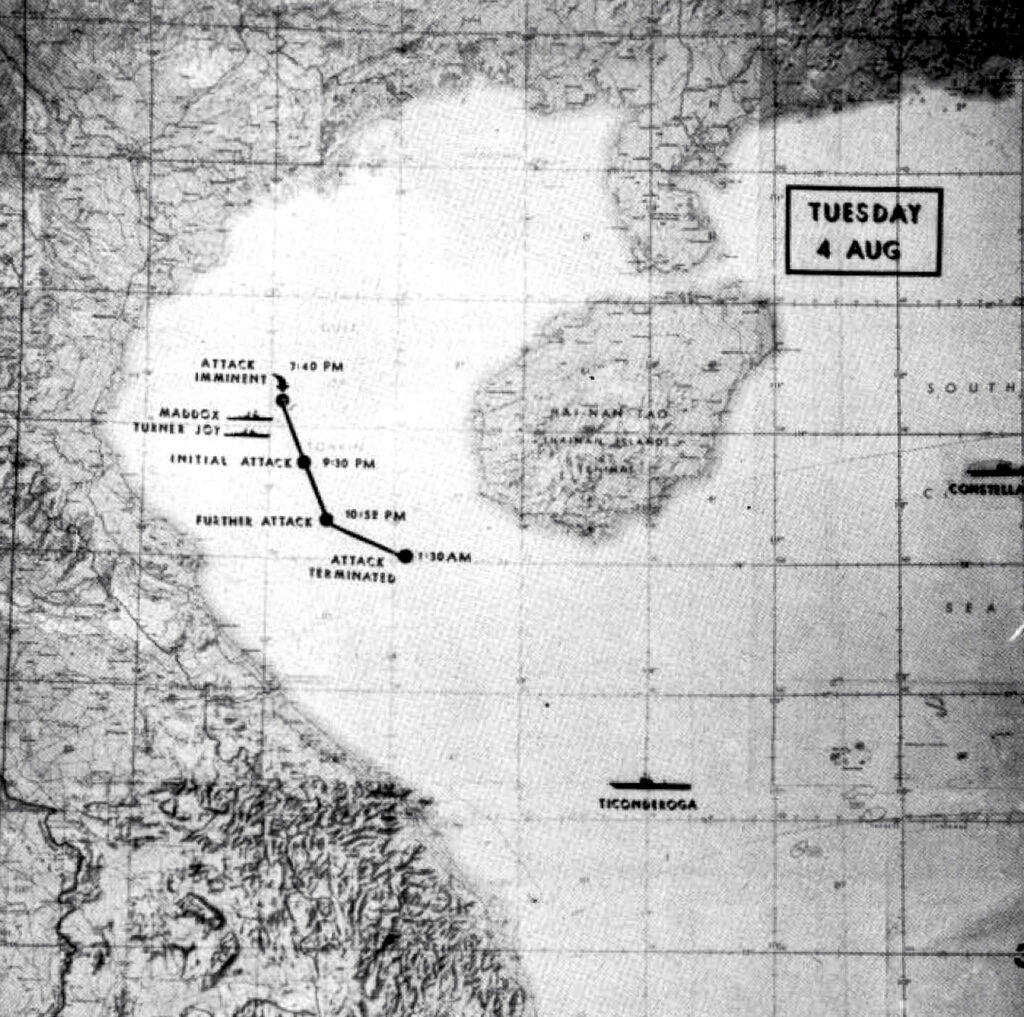

Escorting the Ticonderoga, the Turner Joy was ordered to reinforce the Maddox and jointly continue the DESOTO mission.[2] On the 4th, both destroyers responded to what they thought was a second attack by another group of torpedo boats, taking evasive action and calling in air support from the Ticonderoga. The Turner Joy fired about 250 rounds at a cluster of approaching dots on its radar. False radar images, termed “Tonkin Ghosts,” often resulted from bad weather and choppy seas in the Gulf; the weather was poor on this particular night, and specialists jumpy from the earlier attack may have rushed to conclude that they were witnessing a sequel. Despite the crew’s belief that the Turner Joy and Maddox were under fire again, as well as their assertion that they had sank multiple torpedo boats, reconnaissance missions seeking evidence in the form of oil slicks, fires, or floating debris found nothing in the following hours and days. None of this information casting doubt on the second attack seems to have made it to top decision makers in Washington. The United States commenced the retaliatory Operation Pierce Arrow hours after the supposed second attack, sending 64 carrier-based sorties to bomb Vietnam People’s Navy installations along the coast. Piloting one of those sorties was Everett Alvarez Jr., the first American to be shot down and taken prisoner in Vietnam; he spent the next eight years in Hanoi’s Hỏa Lò Prison. In a joint session three days later, Congress gave President Lyndon Johnson near total authority to prosecute a war in Vietnam under the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, with only two opposing votes out of a total of 504 cast.

Over the years since, due to changing stories and judgments from those involved, Hanoi’s emphatic denial of any torpedo boat missions that night, and official inquiries that cast doubt on early accounts, the events of 4 August 1964 remain something of a mystery. A US Government study concluded in 2005 that the first attack happened, but the second attack did not. Former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara admitted in the 2003 documentary film The Fog of War that the second attack did not happen. Context is helpful. After several years of unsuccessful counterinsurgency campaigns, political repression, and sectarian violence that resulted in President Diệm’s assasination the previous autumn, the Tonkin Gulf Incident took place at a time when confidence in South Vietnam’s long-term viability as a state was at a nadir. It would be easy to conclude that the United States in 1964 was looking for ways to take on a more overt role in the conflict and hand over the job of preventing Saigon’s collapse to the American military. Irrespective of what was on the minds of American policy makers, that’s what happened: they characterized the Tonkin Gulf Incident as an unprovoked communist attack on US navy ships in international waters, opening the door to a ten-year commitment of about 2.7 million American personnel to the cause of defending South Vietnam. The United States got the war it wanted.

The Turner Joy returned to duty in Vietnam many times over the following decade. Pacific missions would last several months, and then the destroyer would then return to its base in Long Beach, California for refurbishment. The ship spent all of its service time in the Pacific and off of Vietnam’s coastline, running Sea Dragon patrols to interdict supplies before they arrived at Vinh or Hải Phòng, shelling I Corps, shelling Chu Lai, or patrolling offshore in the Mekong Delta. The Turner Joy was retired in 1982 and is today docked in Bremerton, Washington. The Maddox, on the other hand, was sold to Taiwan in 1973; it was eventually scrapped in 1985.[3]

Visiting the USS Turner Joy is easy; the ship operates as a floating museum open to the public just about every day of the year. The Bremerton Historic Ships Association, the nonprofit that maintains the Turner Joy, has restored the ship to its Vietnam-era condition and specifications. Bremerton is a small town on the Puget Sound near Tacoma, Washington. It’s the home of the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, which is a 72-hectare facility that has been building, modernizing, and refurbishing US Navy vessels since 1891. At any given time, there will be multiple ships in bay for servicing, and docked here are also several mothballed Vietnam-era aircraft carriers slated for dismantling. One can do a self-guided tour of the USS Turner Joy, and nearly the whole ship is accessible. A few observations about the ship: with rough dimensions of 128 meters by 14 meters, at first glance it’s a large vessel. Yet the Turner Joy usually sailed with a crew of about 300, which seems like an awful lot of sailors to squeeze on board a boat of this size. Rarely were all 300 outside on the ship’s deck at once. Descending below deck, it’s clear that this would have been a crowded ship – most of the Turner Joy’s four below-deck levels are crammed with boiler rooms, engine rooms, supply rooms, radar rooms, generators, multi-deck machinery for reloading the deck guns, and the odd mess hall. That’s it; pretty much all available space is engineered and functional. Interspersed are about 150 bunk bed – foot locker units, and the men slept in claustrophobic quarters with all of the ship’s pipes, generators, wires, control boxes, dials, communications devices, and valves. Below deck, the Turner Joy feels a bit like a submarine. The Turner Joy was also lean and fast. Referred to as “tin cans,” destroyers from this era had extremely thin armor and had a top cruising speed of around 32 knots, which is well nimble for a ship this size. There were no real anti-aircraft guns on the Turner Joy; its main defenses were its ability to move quickly and make sharp turns.

The USS Turner Joy is reputedly haunted. In September of 1964, the ship was shelling NLF positions near Chu Lai when one of its three deck guns misfired. When crew members arrived to clear the barrel, the shell detonated, killing three sailors and wounding three. Psychics and ghost hunters have investigated the Turner Joy and claim to have communicated with spirits on board; the verdict is that two of the sailors that died in the incident now haunt the ship. Tour guides and maintenance workers have also reported seeing shadows, a feeling of being watched, and personal items going missing. The rear deck gun where the accident happened is now marked with a plaque commemorating the three sailors that died that day.

The Turner Joy fired the US Navy’s last round of the Vietnam War. The Paris Peace Accords mandated that all combat operations would cease at 08:00 on 28 January 1973. As the clock ticked towards this deadline, the ship was providing naval support to US Marines under attack on the western half of the DMZ. At about 07:59:15, the Turner Joy fired on an NVA ammunition bunker in the vicinity of the Marines. The round took 45 seconds to travel to and hit its target about 16 kilometers inland, arriving just before the deadline. Coming full circle, the Navy vessel that was so instrumental in the war’s massive escalation also book-ended its conclusion. Despite its monumental role in the opening and closing points of the war, visiting the Turner Joy to explore its pivotal role in the Gulf of Tonkin Incident is a quintessentially postmodern experience: what we commemorate here that took place in 1964 never actually happened.

SB

***

USS Turner Joy, 300 Washington Beach Ave, Bremerton, WA 98337

[1] The Turner Joy was equipped with three deck guns that could fire a 127 millimeter, 32 kilogram shell a distance of 24 kilometers. These self-loading cannons could fire 40 rounds per minute.

[2] United States Navy Rear Admiral George Stephen Morrison was commander of US Navy forces during the Gulf of Tonkin Incident. Morrison was the father of Jim Morrison, singer for The Doors.

[3] The USS Maddox had an eventful life. Launched in 1944, the Maddox supported Pacific Theatre operations against the Japanese in the Philippines, Vietnam, and Okinawa. The ship received a direct hit from a kamikaze pilot off of Formosa in 1944. The Maddox also served throughout the Korean War, providing shore bombardments for UN forces and participating in the 861-day siege of Wonsan, North Korea.

Rear Admiral Morrison was not a player in the Tonkin Gulf Incident (TGI)! Rear Admiral Morrison did not make Rear Admiral until some three years after the TGI. This entire myth of Rear Admiral Morrison being at the TGI should be expunged! I suggest you do your homework before you write Naval History, that you seem to know very little about!

You have a couple factual errors , only one of which I will comment on right now. The 4th photo listed as “Captain’s Conference Room” is a mistake. That is a picture of the Wardroom (officer’s mess). I should know, I lived there for well over a year. The EXIT door with the “Reserved” chain attached to it led directly to my stateroom. I was the First Lieutenant aboard Turner Joy from 1966-1968. The conference room was the Commode’s cabin in the deck above, when he wasn’t aboard. Else we met with the marine spotters in the Wardroom. The point is that is where we ate ALL our meals. We would never have considered calling it a conference room.

My name is Jim Chester and I served on the USS Turner Joy from JAN 71 to JUN 73. I am also a Naval Historian and worked with the 71-73 combat crews of the ship and also worked with the 63-66 combat crews to help get the real truth out about the second attack of the TONKIN GULF Incident of AUG 2-5, 1964, which now has been proven beyond a shadow of a doubt that it did happen. The 2nd attack was done by the Chinese and there was a huge coverup that lasted until 2019. I have seen all the documentary evidence, including the declassified Intelligence message traffic and other documentation purposely stashed elsewhere obtained through FOIA Requests. Your write up about the ship is the old political narrative that was buried purposely by the Federal Government and a book has been written by a key person who was there for the 1st attack and the second attack. I spent 4 1/2 years helping Chad James write that book. Furthermore, your write up is woefully incorrect in a lot of areas. The gun mount explosion took place in 1965 killing three men and wounding a few others. IN 1972 the TJ was out fitted with advanced weapons and advanced fire control and advanced electronic warfare and could easily shoot down aircraft and cruise missiles. During the month of JAN 1973, the TJ fired 10,136 rounds in 27 days of night and day combat, both in North and South Vietnam. We fired the last Strike mission in North Vietnam on the morning of JAN 15, 1973. Cease fire in the North Vietnam came at 0800H 15 JAN 73, via the Paris Peace Talks. This was Operation Linebacker II and we were part of TU 77.1.1

[Surface Striking Force, North Vietnam]. We fought day and night in North Vietnam from 8 JAN 73 to 0800H 15 JAN 73. I have most of the declassified strike message traffic to prove it beyond a shadow of a doubt.

On the last day of the Vietnam War just below the DMZ, we fired 3,003 of 5″ and 187 rounds of 3″. I was there for the last round fired and your write up is woefully incorrect! MARINES WERE NOT ANYWHERE NEAR THE LAST TARGET! Also making decisions on an international scale during the Cold War is hardly mentioned! You make it sound like the US wanted the war and that is NOT the case whatsoever! You may call me at 775-887-0147 for the real scoop! I am also the current President of the USS Turner Joy Reunion Group.

Jim

Thank you so much for your comments and sharing facts with us. I have notified my colleague Stephen who wrote the article. It would be interesting for us to learn more and make some changes to the article accordingly.

/Jonas, founder of namwartravel.com

And you can always contact us at [email protected]

I find this piece of the history very intriguing.