Cherries – my Vietnam story by John Podlaski

I went to Vietnam on August 4, 1970 and after a week of in-country training, I was assigned to the 1/27th Wolfhounds of the 25th Infantry Division at Cu Chi as an infantry soldier (Grunt). My unit operated out of Firebase Kien which was half-way between Dau Tieng and Saigon and not far from the Cambodian border in what the military referred to as III Corps.

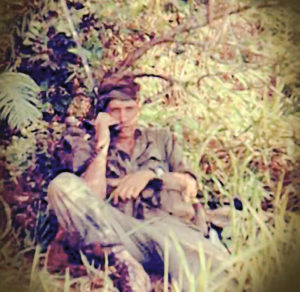

After a few days of acclimation and gathering of supplies, I was flown out to the bush on the next company resupply. There, I was assigned to the 1st platoon of Company A and met up with a couple of former colleagues from AIT at Fort Polk, LA. During my time as a rifleman, I walked point and joined my fellow squad members in daily patrols and ambushes. When our M-60 gunner went home after a couple of months, it was easy to determine who the replacement would be – I happened to be one of the more muscled guys in my squad, and since I was also the youngest, was bestowed that privilege.

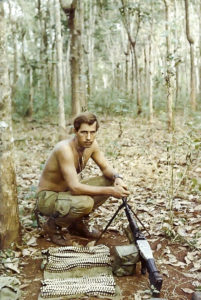

The gun – fondly referred to as “pig” took some getting used to when humping as it weighed 26 pounds, not counting the added weight of extra ammunition (pig food) that was either carried “Poncho Villa” style across the chest or wrapped around my waist. The tradeoffs were that I no longer had to walk point on patrols and was excused from half of the nightly ambushes.

I carried the “pig” for the next four months and then handed it off to a new “Cherry” when the lieutenant chose me to be his personal RTO (radio operator) for the platoon. This was a lot more work and responsibility, but the pro’s seriously outweighed the cons.

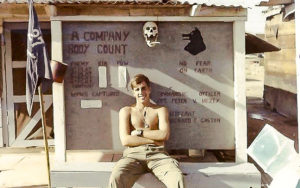

In March of 1971, the 25th Division was leaving Vietnam and returning to Hawaii, their base of operations. Anyone with nine months in-country would join them, all others would be reassigned to other units within the country. I was sent to the far north near the DMZ (I Corps) and reassigned to Company A, 1/501st, 101st Airborne Brigade. With five months left in my tour and temporarily assigned to guard at Camp Vandegrift, I learned about one of the RTO’s in the company command platoon (CP) who was going home when the company returned to the base in a couple of days – I campaigned hard for that position and became the personal radio operator for the Alpha Company commander before their next mission; it turned out to be a position nobody else wanted anyway. I remained in that position until a couple of weeks shy of completing my tour when I was promoted to sergeant and placed on special assignment until it was time for me to go home.

After Vietnam and a thirty-day leave, I reported to Fort Hood and was assigned to HHC 1/12th, 1st Cav Division, heading up the battalion radio repair unit (which turned out to be only me). It was a decent position where I learned to fix PRC-25 radios and to drive APC’s during week-long war games.

The military gave me an early out and I left the Army on December 12, 1971.

*****

Here are some excerpts from my book and website articles:

“…During the Vietnam war, newly arrived soldiers were referred to as Cherries (virgins to war). At least this is how it was in the infantry. I’ve heard other acronyms as well such as FNG (fu*king new guy), Newbie and fresh meat, but they weren’t used as often. A grunt (infantry soldier) remained a Cherry until he lost his innocence, which was usually after his first firefight. I remember seeing war movies growing up where everyone was depicted as a brave warrior, rushing the enemy through a wall of flying steel. Let me tell you that most every soldier still remembers his first firefight. It doesn’t have to just be Vietnam, it could be Korea, WWII, Iraq, or anywhere else where you are put in harm’s way. In my case, I was so scared and felt paralyzed and helpless as I laid on the jungle floor – bullets popping overhead and impacting all around me. Only two thoughts were going through my head at that time: how to sink deeper into this ground and I hope I don’t get hit.

The firefight itself is just a small part of losing your virginity and much of the time it only lasts a few moments before the enemy retreats. It’s what you see afterwards that stays with you forever. Soldiers you just met are laying seriously wounded or dead, flesh and body parts are strewn about, blood is everywhere! Your gag reflex was on overdrive. Rarely did I see a dead enemy soldier in Vietnam as bodies were normally taken when the enemy withdrew. And this made life frustrating!”

“…There is some comparison between a Cherry and a freshman in his first year of high school. Just think about it. You are scared, apprehensive, don’t know anybody, hope you fit in, and you know there is much to learn before you are able to graduate. With this in mind, add to it the threat of death or maiming to your daily routine – somebody may jump out of a locker in the hallway and shoot you (although today that’s not really far-fetched). You must be hyper vigilant just to survive 365 days in this school. And still the learning continued.”

“…Let me preface this post by saying that over 2.5 million U.S. men and women served in Vietnam during the time period of 1959 – 1975. However, only 10% of the total were in the Infantry and ‘humped the boonies’ in search of the elusive enemy, the remaining 90% supported them in various capacities, their tasks, at times, more dangerous than those searching through the jungles. Helicopter crews were held in the highest regard and seen as “saviors” by the infantry soldiers, at times, watching in awe and disbelief while pilots braved enemy onslaughts to transport, rescue, supply and protect those on the ground. Crews were always there when needed – losing many of their own while performing in this role. Other supporting groups, stationed in rear areas or fire bases were also at risk of enemy mortar and rocket attacks, ground assaults or ambushes when traveling outside the base along roads in supply caravans. The ‘grunts’ or ‘boony rats’ had to contend with enemy ambushes and booby traps, sometimes walking directly into well-camouflaged enemy bunker complexes and getting pinned down for hours in the middle of the jungle. It was deadly tour for everyone – no one group was safer than the other! This article will focus only on those Cherries within an infantry unit. Certainly, each military unit received new replacements throughout the war; their indoctrination to war may have been quite different to what is written here.”

“…Imagine, if you will, that most Cherries in Vietnam had graduated from high school within the past year; some never finished and were quickly drafted into the military. In Vietnam, these eighteen-year-old soldiers were thrust into a hostile environment where they had to do things never imagined in their wildest of dreams or even thought of as humanly possible to achieve. Nineteen-year-old corporals and sergeants oversaw squads and twenty-one-year-old Lieutenants and Captains ran the platoons and companies. Turnover was rampant and a soldier with experience in the jungle was highly respected – regardless of age – and in most cases was a lower ranked enlisted man and not an officer.”

“…To understand this feeling, imagine yourself waking up in your bed during the middle of the night; the room in complete darkness – suddenly the bedroom floor in the old house creaks – sending a chill up your spine.

Your mind suggests that a stranger is moving toward the head of your bed – he’s unable to see you but knows you are there. You break out in a cold sweat, your heart begins racing, the beats gaining momentum and pounding loudly like a large drum in the dark quiet of night. You hope the intruder doesn’t hear your beating heart and give away your location. You lay paralyzed, frozen to the spot and too afraid to move your head or sit up to have a look around – let alone get up out of bed to turn on the light (not an option in the jungle). This is real fear! …”

“…Today, I want to write more about another fear these young men had to endure while living in the jungles. Mother Nature had created many wonderful things over time; some were beautiful, and others were downright frightening. The jungles of Vietnam were home to every creature, beast, and insect known to man. Some veterans attest to seeing tigers and elephants in the boonies, but I can’t say that I saw neither. However, I had seen many wild boars, cobras, small and deadly viper snakes, different spiders and a few boa constrictors. Someone once said that Vietnam was home to 100 different species of snakes – 98 were poisonous and the other 2 could crush a person to death.

Tarantulas (and other species / sizes of spiders – some the size of dinner plates), red ants, and black horseflies all hurt like hell when they bit. Bees, wasps, hornets, centipedes, millipedes, lizards, frogs, rats, scorpions, land and water leeches, orangutans, spider monkeys, bats, and hordes of mosquitoes attacked us whenever we entered their domain. The liquid bug juice supplied by the military kept many of the flying insects from landing on bare skin but did nothing to prevent those long-beaked malaria-carrying insects from biting you through clothes. I’d try to cover my head at night with a poncho liner to keep the mosquitoes away, but it was hot and uncomfortable and there was no escaping the constant buzzing in your ears as the blood-thirsty swarms hovered above my head, awaiting patiently for an opportunity to taste the sweet nectar.

Another heart stopper is when you felt something moving across your body during the night – there were no lights to turn on or flashlights available to investigate – besides, any light or noise in the dark jungle would be a beacon to those who want to kill me. You took your chances and either swatted, brushed, jumped up from the ground, or just left it alone. Some of these creatures had claws that gripped you; swatting at them usually pissed them off and resulted in a retaliatory bite, sting, or pinch. Most of the above were poisonous and could make one very sick or even kill.

Someone once said that what you can’t see won’t hurt you. That might work for your peace of mind during the night, but let me tell you, these creatures were always found in the damnedest of places first thing in the morning. You could find them in your pockets, boots, helmet, rucksack, canteen cup, or laying with you under the warmth of your lightweight poncho liner blanket. A search and destroy effort was usually the first thing on the agenda every morning.”

John keeps on writing, sharing his and other’s experiences, make sure to check out his website for even more stories and facts you never knew about on: https://cherrieswriter.com/

To buy John Podlaski’s book’s please click on one of below links:

Paperback:

Kindle:

Back to Stories from the war>>>