Phong Nha Ke Bang

Phong Nha Ke Bang National Park in Quang Binh province is one of the more recent entrants into the field of big tourist destinations in Vietnam. The park features a massive natural underground cave network that rivals anything elsewhere in the world. Thanks to the discovery here and designation of Son Doong Cave as the largest cave in the world in 2009, tourist numbers have ticked up in this heretofore quiet part of the country and investment has kept pace. Phong Nha’s caves, karst formations, mountains, and rivers make it one of the most breathtaking parts of Vietnam.

Lesser known, however, is this region’s role in the Vietnam War. During the war, the Phong Nha area was one of the North’s major staging areas for northern soldiers and supplies transiting to the front in the south. Soldiers would come from all over northern Vietnam and supplies would come from Hai Phong via a network of north-south roads in North Vietnam. Phong Nha was an entrepot; supplies would be stored in caves and then be re-loaded onto smaller vehicles, bicycles, or pedestrians for the trip south below the DMZ.

PAVN soldiers would spend a few weeks of final training here before heading to the front. They might get a few days off during this time to relax in a scenic part of the country. Before the United States committed regular troops to an expanded war in 1965-66, infiltration south from Phong Nha took place all along the DMZ. After the US started building a bulwark of large bases and strong points along Route 9 in Quang Tri, however, most of those infiltrations were interdicted and stopped. Khe Sanh Combat Base in particular was effective at stopping the flow of troops and supplies into the south.

A large part of the Phong Nha story is one of northern Vietnamese women volunteers for the war effort. The majority of the infantry troops sent south along the trail into battlefields in the south were men. Most of the volunteers that kept the Ho Chi Minh Trail open, defused bombs, filled bomb craters, managed waystations, moved supplies, ran hospitals, built infrastructure, and operated anti-aircraft guns were women. Their stories carry strong themes of individual agency: many volunteered for this duty because they, like most others that fought against the ARVN and the Americans, envisioned a future in which they would be able to live, prosper, and raise their families in a peaceful Vietnam.

Along the way, they sacrificed their youth, their families, and their lives or their health for this objective. The Government of Vietnam estimates that over 170,000 volunteers led the national war effort in the north by keeping over 2200 kilometers of the Trail open and operating anti-aircraft defenses at about 2500 key points along the supply line. About 70% of these volunteers were northern women. Most around the age of 19 or 20 years old, they often came from farm households, and most had a primary school education at best. They were brave and patriotic, and they are as responsible as anyone for what the Democratic Republic of Vietnam was able to achieve in the war. If there is any place symbolic of the Vietnamese woman’s contributions to the victory, it is Phong Nha. It is in Phong Nha, Ham Rong Bridge, Ha Noi, along the length of the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and dozens of other contested places in North Vietnam where they were responsible for keeping the roads open and the land defended.

After the American buildup began, North Vietnam re-routed its major supply route through Laos and refurbished and built new sections of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. On any given day during the war, there would be around 2,000 laborers building and repairing the Trail. By 1975, there were thousands of kilometers of trail, and most of it was cobblestoned. Phong Nha remained the staging area after the shift to the Lao route, and new roads were built to carry troops and supplies west into Laos, and from there, south for eventual re-entry in Vietnam below the DMZ. One in particular was Highway 20. Named for the average age of the engineers and laborers that built the road, Highway 20 was the center of the logistics network in Phong Nha. It connected to hidden roads as well as pontoon bridges, boats, and trucks that were hidden in caves during the day. The United States heavily bombed the Phong Nha area because it was the center of this network. So much so that PAVN anti-aircraft shot down hundreds of American planes over Quang Binh province during the war. Upwards of 30% of the ordnance these planes dropped never went off. There is still a serious UXO problem in the Phong Nha area.

Around Phong Nha there are numerous sites that survive from the war. And evidence of the war survives the passage of time and the jungle’s reclamation of this supply and defense network. There are numerous karst cliffs that have been sheared off after direct hits from missiles fired from US jets to cause landslides and temporarily close roads. There are holes burrowed into roadside rock walls that once sheltered Ho Chi Minh Trail volunteers assigned to keep the roads open. There are American bombs that now function as bells hanging outside churches that were previously used for communications and emergency warnings along the Trail. And this being a region of caves, there is a network of PAVN caves that served as factories, storage spaces, living quarters, and hiding places for soldiers and supplies. Many of these caves are off-limits or extremely difficult to find and enter. As the Ho Chi Minh Trail criss-crossed through Phong Nha, pretty much any road you find yourself on was once part of the Trail. This one you definitely need a guide for.

Giap’s Cave

This small cave requires a hike up a very steep trail for 50 meters or so. It was nicknamed “Giap’s Cave” because General Vo Nguyen Giap himself visited PAVN soldiers here back in the late 1960s. The entrance to the cave is about 4 meters by 3 meters and the interior is small compared to others in the area. The PAVN built a stage and amphitheatre inside the cave, which was used for performances, political discussions, and award ceremonies. Photographs from the north during the war aren’t numerous. They’re usually black and white. Caves would have been lit up at night for group sessions by candlelight or lanterns. Soldiers and volunteers would have been squatting on the floor of the cave in rubber sandals made from truck tires and army clothing, watching a performance or listening to a patriotic lecture. Vietnamese are typically excellent orators and singers, so there would have been some spirit in the room. Soldiers and volunteers would have demonstrated esprit de corps and enthusiasm for their undertaking.

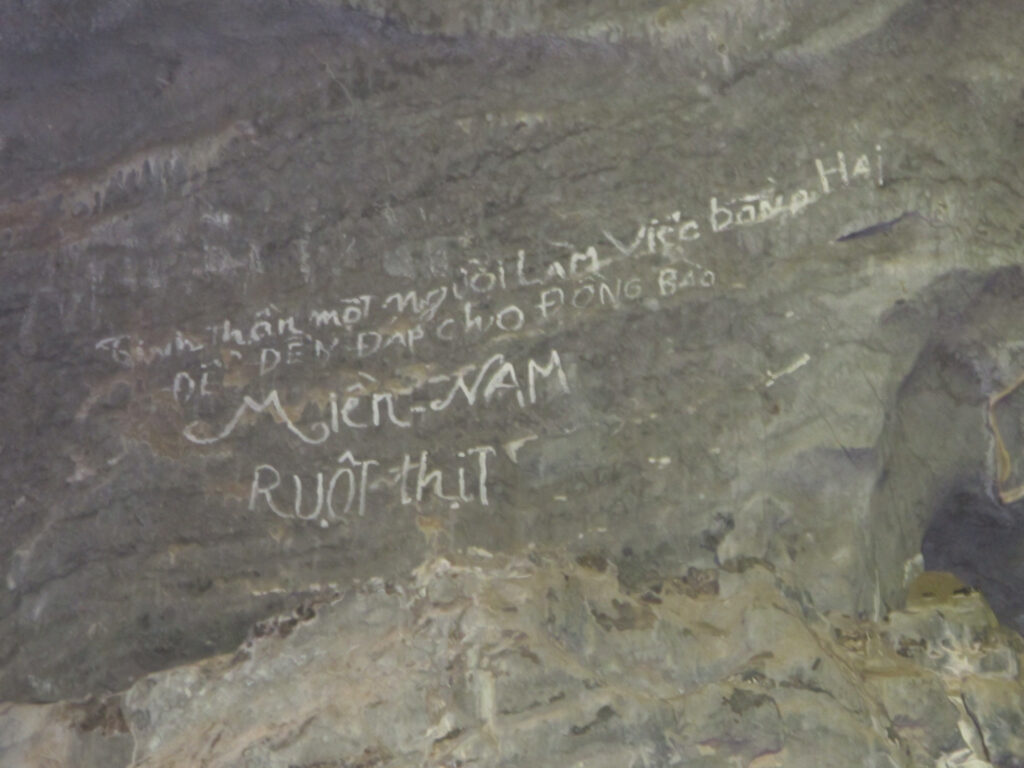

There’s graffiti and patriotic slogans on the walls in these caves, much of it written by soldiers and volunteers during the war. Along with graffiti on the walls of the cave, the stage is still there, unchanged over the past 45 years or so. Parts of the stage floor are even worn down. It’s been used. Parts of the rock wall around the entrance are sheared off, most likely from direct hits from US aircraft.

Khe Gat Airfield

In Quang Binh there were a handful of jungle airstrips used by the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, though they weren’t nearly as busy as those of their counterparts in the South. PAVN engineers built Khe Gat Airfield near Phong Nha in 1969. The airfield straddled the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which enabled access to supplies and anti-aircraft cover. The PAVN disassembled two Soviet-built MiG-17s and brought them down the Trail in early 1972. The planes were re-assembled at Khe Gat and flew a bold attack mission against US Navy warships in the Tonkin Gulf in April of that year, scoring a direct hit on the destroyer USS Higbee with a 500 lb bomb which shattered one of the ship’s guns. Incidentally, the USS Higbee was also one of the vessels involved in the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Incident. As the local story goes, the pilot that scored the hit in 1972 bailed out over the Gulf of Tonkin as US Navy aircraft gave chase. He was rescued by a Vietnamese fishing boat. He quickly became a hero not only in Vietnam, but also among allies in Cuba, Eastern Europe, and the Soviet Union. In 2010 a Cuban construction team arrived in Vietnam and built a road on the spot of the former airfield, in recognition for its role in the war.

Khe Gat Cave

Overlooking the site of Khe Gat Airfield is a cave that had a support function to both the Ho Chi Minh Trail and the airstrip. It’s well hidden in between two tall karst cliffs, but that didn’t deter United States aircraft from finding and bombing the location. This cave requires a short steep walk in between the karst formations, and one encounters a handful of bomb craters on the way up.

Two of them are gigantic, probably 6 meters deep and 15 meters across. Around 1967-68, this location was probably bombed just about every day. This cave also has a stage and a natural amphitheater inside of it. Initially one might guess that the cave has similar dimensions as Giap’s Cave, but a right turn near the stage reveals a second large tunnel of probably 3 meters height that stretches back about a hundred meters further inside the mountain. It was likely here that supplies were stockpiled and soldiers lived, ate, and slept.

Ruou Factory Cave

Near Highway 20 is another PAVN cave that is so exquisitely hidden that it was necessary to ask a local man and ask him to take us there. Off a country road and through a muddy field we rode motorcycles until we came upon the entrance. During the war, this cave served as a rice wine factory. Rice wine is a customary Vietnamese tipple that is easily manufactured. The factory was well hidden to protect it from American bombs. Rice wine distilled here served the dual purpose of both supplying troops in the Phong Nha staging area and supplying PAVN troops in the field in South Vietnam. Big jugs of rice wine would be walked down the Ho Chi Minh Trail to base areas at the front.

PAVN soldiers didn’t take their R&R in exotic places like the Philippines or Japan as the Americans did. Most took their R&R in the field, usually just far enough from the front or in rear areas in Cambodia and Laos. Some would spend a few days drinking rice wine in Quang Binh for their break, and then they’d return to their units. Rice wine from this factory essentially was their R&R, in other words. Evidence left behind in this cave is scarce, but there are a few things. First, there’s a fair bit of graffiti on the walls inside the cave, and some of it clearly suggests it was written during wartime. Someone had written a “67” on the wall, and someone else wrote “Thịnh thân một người làm việc bỗng hai đi đến đắp cho đồng bào miền nam ruột thịt”, which roughly translates to “one person working for two, for our southern brothers flesh and blood of the same country.” There are a few steel racks that were drilled into the rock walls, presumably for hanging distillery equipment. Otherwise, there are a few oddly-shaped boulders that look like they would have been used to support vats of rice wine in various states of preparation. Like the other caves, there is also a stairway carved out of rock that leads part of the way up the hill to the entrance.

For anyone that’s read about the war from the northern perspective or who has viewed photographs from this time period, this cave is demonstrative. You know that you’re in a consequential place. This is a simple factory that probably operated for most hours in the day, under candlelight or wall lanterns, with workers manufacturing wine for the troops at the front. This would have been a patriotic and ideological enterprise, and there was probably a great deal of camaraderie here.

Tam Co Cave

Highway 20 winds its way in and around Phong Nha Ke Bang National Park, and given the karst formations and steep mountains, it has to be one of Vietnam’s most stunning stretches of road. Along Highway 20 is a memorial site for Ho Chi Minh Trail volunteers that died here in 1972. Over the years, it has evolved into a shrine where Vietnamese come to pay their respects to all that sacrificed along the Trail during the war. But the story of the cave is especially poignant. This location had been a waystation along the trail throughout the war. Volunteers lived in a cave nearby and their role was to repair the Trail after bombing runs.

They also took care of the soldiers and volunteers that passed through on their way to or from Laos. Other volunteers operated an anti-aircraft battery across the street from the cave. “Tam Co” means “Eight Ladies,” and on one day in November 1972 US B-52s attacked the waystation, destroying the anti-aircraft battery and bombing the entrance to an adjacent cave shut. Inside of that cave were eight female volunteers between the ages of 18-20 from a village in Thanh Hoa province. They fled to the cave to avoid the bombs. Despite numerous attempts to re-open the cave and rescue the volunteers, there was simply too much destruction and rubble to clear. After nine days Trail volunteers could no longer hear voices from behind the landslide.

In 1996, the Government of Vietnam finally opened the cave and found the remains of the eight women; they were sitting in a circle together when they perished. The government returned the remains of the volunteers to Thanh Hoa and built a shrine at the location. Today it is a well-traveled and solemn spot, and inside the shrine are preserved some of the personal items found in the cave in 1996. The actual cave and another altar are situated next to the shrine. The cave is a sacred place and thus entry is prohibited.

Logistics and other information

For the past ten years or so, there has been lots of tourism investment in the Phong Nha area, so it has become a very easy place to access. Roads are good, and the area is served by the Dong Hoi Airport, about 30 kilometers away. There are many hotels and restaurants in this area. Phong Nha Ke-Bang National Park attracts more and more eco-tourists every year, and those visitors interested in history would be wise to add a few days to their itinerary to learn more about this fascinating part of Vietnam. Well-preserved original North Vietnam war sites are something of a rarity, as the conditions of the war in the North didn’t permit much construction of permanent war infrastructure. Furthermore, the stories about the Phong Nha area are predominantly local stories. One rarely reads much literature in English about what life was like in caves for PAVN soldiers and volunteers.

Author’s Note:

Few of the places in this article are on a map. A good guide is a must. And there aren’t many good guides in this area. Thus, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention and thank Ben and Bich from the Phong Nha Farmstay for their help to make this compelling tour happen. They helped me out with tour guide references and historical information, which enabled me to unlock this region’s secrets a bit. Having lived there for 13 years, Ben is a Phong Nha encyclopedia. The Phong Nha Farmstay is a country guesthouse in the center of this region that is comfortable, beautiful, and budget friendly. They also run what is easily the best restaurant in the region. The owners are Australian and Vietnamese, and the resort is located in the Vietnamese owner’s home village. They know Phong Nha, its stories, and the local community as well as anyone. For the record, I wasn’t offered, nor did I accept, anything from them for this endorsement. It’s as simple as this: a strong recommendation of this hotel and this local family to anyone interested in the history of Phong Nha.