The Fall of Saigon – through my eyes

My name is Trang, I’m the only child of a middle-class Vietnamese family. I was born and raised in Saigon.

In January 1968, the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong launched the countrywide Tet Offensive that devastated parts of my country but mostly devastated Viet Cong as a fighting force. After the Tet Offensive a general mobilization was proclaimed in the Republic of Viêt Nam (RVN).

The following year I volunteered to serve in the Navy. The first step was four months of basic military training at Quan Trung military training center run by the Army near Saigon. Thanks to my English, however, I qualified for training as an electronics technician in the United States and my first trip on an airplane was a Braniff Boeing 707 across the Pacific Ocean to Travis AFB in California. I trained in San Diego and San Francisco on basic electronics and radar before returning to Vietnam and a job at the Hai Quan Cong Xuong shipyards repairing radars.

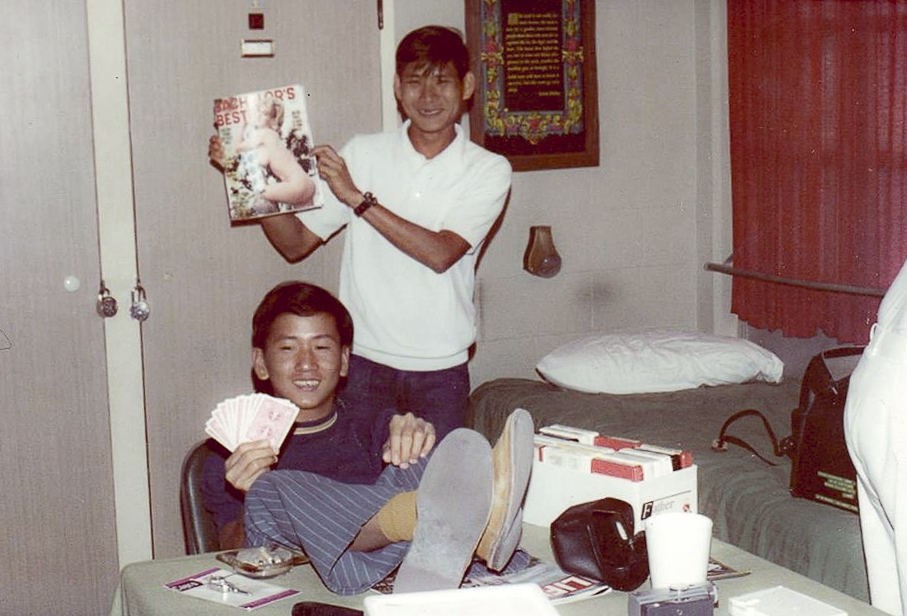

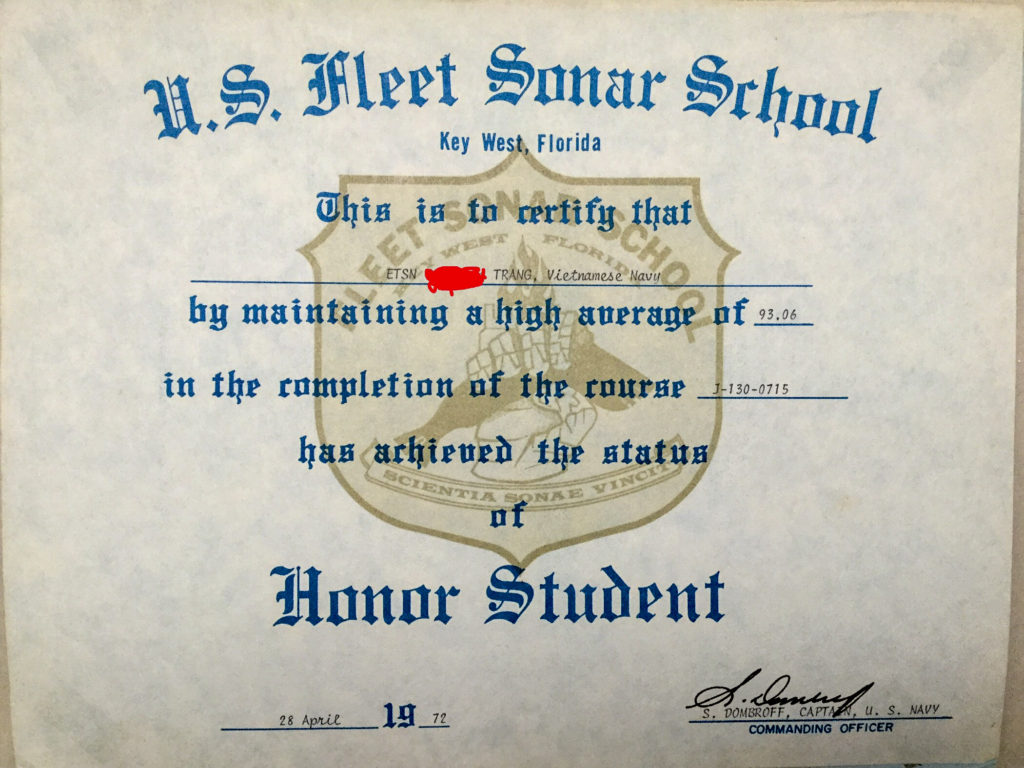

After nine months, I was sent back to the U.S. for further training, first in Illinois then later Key West, where I took a 10-month course on the SQS-29 sonar as well as the firing control system comprising of hedgehog, depth charge, MK-46 torpedo and ASROC.

Back in Viêt Nam, I was tasked aboard the destroyer HQ4 that participated in Operation Market Time. I sailed with this ship for six months, then I was ordered to report to the Saigon Navy Headquarters for assignment at the Bureau 6 (phòng 6), the fleet logistics in electronics, where I stayed until the end of the war. My job at the Navy HQ was an office job that had very little in common with my qualifications, nevertheless it was essential for our crafts both seagoing and inland.

On the morning of April 8th, 1975, the day’s monotony was broken by a lone F5 Tiger jet fighter that bombed the presidential palace, but caused only slight damage since the bombs missed their intended target. This was only a prelude, however, for more serious things to come.

With the NVA closing in on Saigon, tensions were running high among all of us. On April 25th, I was called in to be questioned by the military security (an ninh quân đội) about my use of a personal pair of binoculars. I told them they were to pass the time since I was forced to stay at the headquarters around the clock the past few days. They also checked my locker and asked about the presence of an AR-15, I replied that it was issued to me the day I was transferred to Bureau 6.

An officer who worked with me told the security staff that the binoculars were for watching the girls passing by down on the street below. They eventually ended up confiscating my binoculars with no other charges against me. Somebody must have reported me for being a double agent.

April 28th was a beautiful sunny day in Saigon and I remember wishing I could go window shopping with my wife but instead I was here in my office with the military staff. Our civilian secretaries were ordered to stay home.

In the afternoon around 1500, loud explosions were heard and black smoke rose in the distance. Only a few kilometers away from the Navy headquarters, Saigon’s civilian and military airport Tan Son Nhat had just been bombed. Minutes later all hell broke loose as all the guns of the ships moored in front of the RVN Navy headquarters and along the Bach Dang pier opened up in a terrifying staccato of gunfire. Someone yelled AAA fire, I grabbed my helmet and my AR-15 and dashed to the balcony to see what was going on. A flight of three A-37 Dragonfly light attack aircraft led by Nguyên Thành Trung, the renegade pilot that bombed the presidential palace 20 days before, passed overhead at about 150 meters altitude in the direction of Thu Thiem on the other side of the river.

Scores of red tracers lit up the sky forming an impenetrable web, but way behind the bomber formation. The chief petty officer next to me emptied the magazine of his M16 at the fleeing aircraft while I held my fire because I knew the small caliber of my projectiles wouldn’t cause any substantial damage if by chance they found their marks. Moments later a C-130 flew over the Saigon river in front of us and was the target of our ships, but it too escaped. That night, like everyone else, I slept in my office on the very desk I worked on. Around midnight, we were awakened by whistling sounds followed by loud explosions.

Tan Son Nhat was attacked once again, this time by 122 mm rockets. The next morning it was an endless ballet of helicopters that marked the beginning of operation Frequent Wind, the choppers came from aircraft carriers off the coast, south of Saigon to pick up Americans and Vietnamese civilians that had worked for the Americans.

At one point, high in the sky I saw a pair of jet fighters that I had never seen before. I later identified them as F-14 Tomcats, performing a Combat Air Patrol mission. Tensions were high as panicked people tried to enter the perimeter of the naval installation complex in hope of boarding a fleeing ship. The complex was normally off limits to civilians. Throughout the day, shots were fired in the air by the RVN military police Quan Canh and sailors that guarded the entrance in order to hold them back. While chaos reigned on the ground, an AC-119K gunship flew overhead provided supporting fire to hold back the advancing NVA. Eventually it was hit by a shoulder fired, heat seeking SAM 7 missile and went down in flames, I did not see any parachute. In the afternoon as the situation deteriorated, I called my family to ask if they wished to leave Saigon on a Navy ship, my father refused my proposal as he believed in a three-party government when the war would be over. That evening the sky was blazing red, a sight that I have never seen before. “Is this a bad omen?” I remember thinking. With a handful of diehards, I spent the last night defending the headquarters. There was more shelling, as one might expect, but luckily we were not attacked by the NVA.

On April 29th, I went to the military security office located on the first floor in the Navy headquarters building to get my binoculars back, after some discussion they handed them over. On my way back to the office I stopped by the armory to see if they had a CAR-15 available. I wanted to trade in my AR-15 to this shorter and smaller version of the M16. I wanted to have a more effective weapon for my personal protection for when it was time to leave the headquarters and go home. Unfortunately, all they had was old World War II-era M1 carbines

In the morning of the 30th, as it was clear to all of us it was over, we said goodbye to one another and went home. I decided to go home unarmed, my rifle was too large to carry on a motorbike and difficult to hide.

I wanted to pay a visit to my uncle who was a retired RVN police officer. He had a house on Nguyễn công Trứ, not far from Bến Thanh market. I remember is I passed in front of the Bến Thanh market, down along Trần Hưng Đạo street then turned left to Nguyễn công Trứ.

When I arrived, I was greeted by my uncle in person, his wife and some of my cousins. We chatted for a little while, but they didn’t seem to realize the war would soon be over, at least not this way.

After we had said our goodbyes, I then rode to my home in Gia Dinh. On the way I passed an abandoned M-113 armored personnel carrier, it had a hole the size of a tennis ball in its hull with spalling around the impact. It had probably been hit by a HEAT rocket fired by an RPG. There was more activity than usual in the streets but no sign of panic whatsoever. I don’t recall seeing any scenes of looting. I arrived home uneventfully. We lived at Bình Thạnh district by the Saigon river, and from our bank of the river we could see the highway bridge that leads to Bien Hoa. The NVA were on the opposite side and their artillery was pounding Saigon. All of a sudden, a shell landed in an apartment building a few hundred meters away. They announced that if we do not surrender 4,000 shells will be fired daily into the capital.

Two VNAF A-37 aircraft emerged from nowhere at low level to attack the enemy position near the bridge, they carried four bombs each under their wings, I vividly remember these details. Minutes later a tank burst into flames as the result of a direct hit. The planes never reappeared, they probably did their last sortie before leaving the country for the safety of Thailand. I then joined my father listening to the radio for further news until the announcement of President Duong Van Minh to our troops to surrender unconditionally. After the announcement, I saw a large group of NVA soldiers crossing the river to reach our side.

The war was over, a bamboo curtain had fallen on south Viêt Nam and its hapless souls.